Some of the Ha-ma-yas Guardians take their research skills to the next level: underwater.

“I’m really happy I did the dive course. It’s not easy, and you have to dedicate the time and work into it, but if you have a passion for the marine environment and want to get a better understanding of it, then it is really worth it.”

—Caelan McLean, K’ómoks First Nation Guardian

Over 2024 and 2025, with logistical support from the Nanwakolas Council and the A-tlegay Fisheries Society and funding from Environment and Climate Change Canada, several of the Ha-ma-yas Guardians (Caelan, Jordon Labbe and Montell Henderson-Brown (Wei Wai Kum), Anthony Seville (We Wai Kai), and Telisa Puamau and Caitlyn Puglas from Mamalilikulla First Nation) obtained their commercial dive certification. Taking the 200+ hour course was a big commitment and very hard work but has also been well worth the effort for all of them.

Photo credit: Jordon Labbe, Wei Wai Kum Guardian

Getting up close and personal with kelp

The stimulus for organizing diving training and for Guardians to become certified arose from kelp research that has been conducted by some of the Nanwakolas member First Nations since 2018. Kelp, which grows almost everywhere in the marine environment in the Nations’ territories, is a vital indicator species of marine habitat health, and supports many other ecologically, culturally and economically important species.

As many as 350 marine species—perhaps even more—can exist in a single kelp bed, which can act as a nursery to spawning sea life, such as herring which lay their eggs on kelp, and a safe hiding place from predators for other species. The research into its health, abundance, and range is not only helpful to understanding the overall health of the territories but to support stewardship decision-making by the Nations in relation to all of these species, including the kelp.

Marine ecologist and experienced diver Markus Thompson has been working with Nanwakolas and the Guardians on kelp research since the beginning. He explains: “We began in 2018 with surface surveys, mapping where the kelp beds were. Then the Nations selected several beds to monitor in detail, checking for things like density of the beds, what species are present, substrate, temperature, and salinity, and other observations relevant to kelp health.”

The missing link

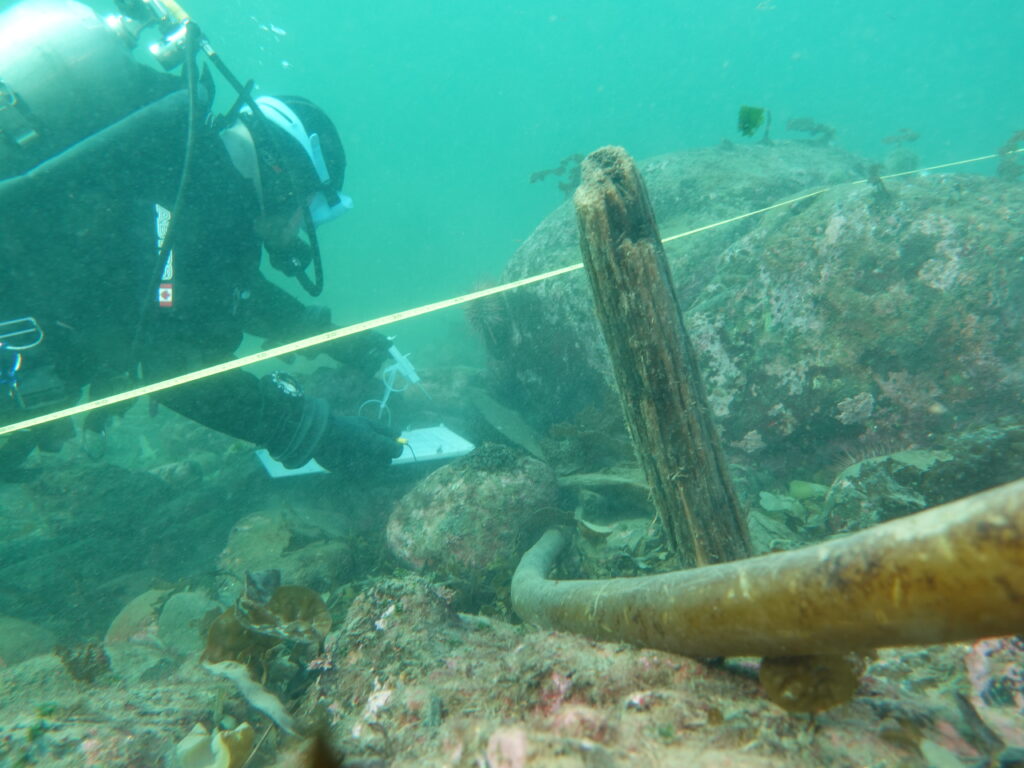

The next logical step was to have a look at what was happening underwater: “You can see what is happening in a kelp bed from the surface to a certain extent, but you don’t really know why that kelp bed was changing over time, if it was,” says Markus. “In order to do that effectively, you need to get underwater to map biodiversity, to quantify the number of urchins, and urchin predators such as sunflower sea stars. All of these details are important in understanding how kelp is changing over time, and it was missing because we didn’t have Guardians underwater.”

K’ómoks Guardian Caelan McLean has been doing the kelp surveys since the beginning. Taking the dive training just made sense to him: “I was really happy to do the dive course, as I realized this was the next step in doing the kelp research,” says Caelan. “We had years of data from the surface surveys, and it was time to go to the next level, which was to have a look at what is on the bottom of those kelp beds to complete the picture. That’s why when the dive training was offered, I jumped on board so that I could see that side of the kelp at last.”

Getting out of your depth

The training is far from easy, says Markus. “There’s a lot of information they are required to learn, such how to identify species—which is one thing to do out of a book and another thing entirely underwater; species are often camouflaged or colored or textured differently than you might see in a book. Guardians also need to know how to properly set up a transect underwater and how to effectively quantify the number of species that they’re identifying, including kelp, invertebrates, fish, of course, urchins, and sunflower stars. It takes time to build those skills.”

Of course, there is also just coming to grips with learning how to dive. Before even being able to take the commercial diving training, says Caelan, he had to do a basic open water course to learn the rudimentary skills required, like how to handle his breathing regulator, before getting into more serious diving requirements. “It was definitely scary and challenging at first,” he admits. “The open water course was my first time diving, and I drank a bunch of ocean water! One of the first safety skills you have to learn is taking your regulator out and dropping it, then practice recovering it. I would always half-panic and end up swallowing a lot of salt water,” he grimaces. “But you get used to it and learn to keep your composure and be methodical and calm before you start reacting.”

The course is a mix of classroom time spent learning about the equipment—the oxygen tanks, regulators, and the heavy-duty neoprene drysuits required in the coast’s frigid waters—and how to maintain them properly, as well as understanding the mathematics required to calculate dive times. That is working out how long you can stay underwater depending on how deep you are going, how much you are carrying, and whether you will be doing work that requires a lot of physical exertion or simply counting species, for example. They also learned about hazards like decompression illness and potentially, some wildlife.

“Then in the field you practice your skills underwater. You learn how to handle your equipment while carrying other gear like notepads, measuring equipment and so on,” explains Caelan. “There are safety skills you have to practice, like swimming with an unconscious dive partner, learning how to use lift bags to carry specimens or debris to the surface, and tying knots underwater. In the final exam,” he adds, “your mask is blacked out, and you have to demonstrate that you can tie knots even in zero visibility.”

A challenging environment

Photo credit Jordon Labbe, Wei Wai Kum Guardian

“It’s really fantastic to see the Guardians build confidence in their underwater skills while getting out there and doing the work,” says Markus. “It takes a lot of expertise and skill to dive in the marine environment in BC. These are some of the most challenging waters in the world to dive in. The water temperature is a factor, for a start, requiring drysuits to prevent hypothermia. On top of that, divers often have to deal with swell, and current. The strong currents here limit how much time you can spend in the water. At full tidal flow they can run up to 15 knots, while a diver can only work effectively in a one knot current or less.”

The divers typically wait for slack tide, when the tide is slowing down as it changes direction. “But tides don’t always match the current speed,” explains Markus. “You really need to know how that applies at every location where you are diving.” That’s because current behaviour changes from site to site, creating whirlpools in some places or behaving differently in general because of the underwater topography. “The Guardians have had to learn how to deal with that, and at the same time handle data sheets to record species or take photos. There’s a lot going on for them. They really have to work hard.”

Curious wildlife can add to the challenge: “Sometimes divers have to contend with wildlife that might be interested in what they’re doing; seals and sea lions, for example, will check out what the Guardians are doing, or curious octopus will start to play with their equipment,” says Markus. “It’s definitely something I have in the back of my mind whenever I’m diving,” agrees Caelan. “Seals aren’t too bad but sealions can definitely want to interact with you.” Whales are another concern: “We had one dive delayed for an hour because there were eight orca cruising by,” he says. “When I am dressed up in dive gear looking just like a seal, I do NOT want to be in the water with an orca!”

More than just kelp research

The Guardians are putting their dive certification to good use in other applications as well as the kelp research, such as salvage operations and archaeological surveys. In the K’ómoks estuary, for example, Caelan has been supporting work in the Kus-Kus-Sum Project, a joint initiative with K’ómoks First Nation, the city of Courtenay and Project Watershed aimed at converting a former industrial sawmill site into a healthy, naturalized tidal marsh and riparian estuarine ecosystem. “We’re diving to check sites where a barge is being brought in to remove a wall, to make sure there are no fish traps that the barge might damage.”

The Guardian divers from the different Nations also work together when it is helpful to deal with, for example, an emergency situation in the territories. “When a houseboat sank in Gowlland Harbour on Quadra Island last year, for example, some of us worked together to do the salvage work and clean-up,” says Caelan. That’s also challenging work: “The visibility was really poor and there was a lot of garbage to deal with. You also had to be really careful not to pick up something with a nail sticking out that might puncture your drysuit.”

Caelan has enjoyed being able to work with Guardian divers from the other Nations on clean up operations like this, and on the kelp work: “It was really nice to get the same training as them, and to know we’re doing the same thing, just in different areas. I like the thought of knowing wherever they’re working and wherever I’m working, we both have our eyes open to the same issues and concerns, like species at risk. It’s cool to know that we’re all looking out for the same thing and have the same values.”

Totally worth the hard work and challenges

Photo credit Jordon Labbe, Wei Wai Kum Guardian

The Guardian trainees say that there is a “huge difference” between just looking at kelp on the surface and being able to see it at seabed level, where they can observe its health in the ocean, and see what kind of species are using the kelp as their habitat. Their appreciation for being able to learn the skills needed to do that work, to be able to contribute their knowledge to their Nations this way, and even to be able to do other kinds of work that require diving skills, like cleaning up after a small vessel sinks, is equally huge.

“It’s been great for me to see the Guardians really dialing in to all these skills and becoming experts, not just at diving but at doing the underwater monitoring,” enthuses Markus. “This is really hard work, and they have just nailed it.”

“For me, it’s really fantastic to be able to see where all the fish hang out down there,” says Caelan. “I’ve done a bit of fishing and now I can see their habitat and hang out with them in their own space. And now I can also provide useful information about them to my Nation, because I have learned to identify the different species and understand what is happening in the marine environment much better than I did just working on the surface. That’s very cool. I am so glad I did the training. It was worth all the hard work and the scary moments!”